From Woodstock to Weston

September 11, 2018 — Weston Historical Society's "Westonstock" event evoked memories of the legendary Woodstock festival, held in 1969. Several Weston residents attended the original. We thought you would enjoy hearing some of their stories.

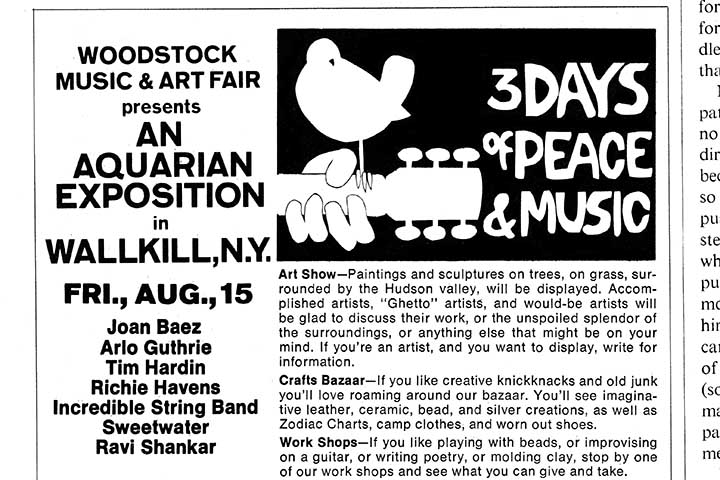

Dan Burstein was a 15-year-old kid in southern California who loved rock and roll. He was cool enough to subscribe to the Village Voice, where one day he spotted an ad for the Woodstock Music & Art Fair in Wallkill, New York, set to begin August 15, 1969. It was billed as an "Aquarian Exposition, 3 Days of Peace & Music," and featured some of the biggest acts of the time.

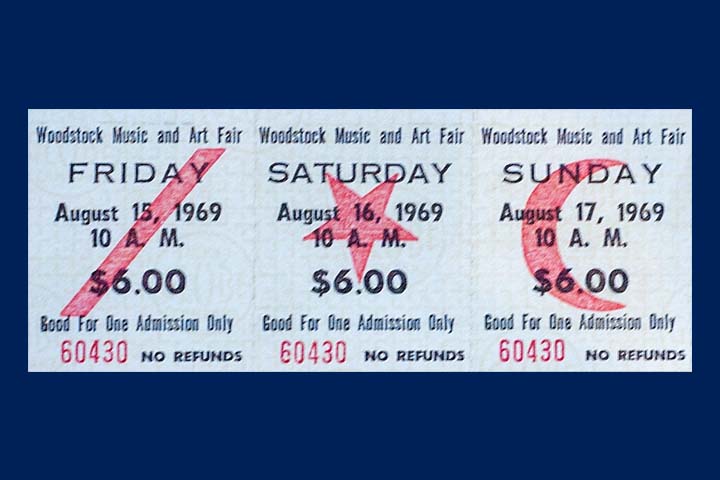

Tickets were $6 per day. Mr. Burstein gave his mother $18, asked her to write a check, and convinced his parents that a trip to New York would be good preparation for going away to college and an opportunity to see his sister in Boston.

The tickets you see in the photo are his. He flew east to the festival. By the time he got to Woodstock, they weren't quite "half a million strong," and tickets had become keepsakes.

The festival was conceived by four New York entrepreneurs, who originally intended to build a recording studio in Woodstock, then shifted their thinking. Instead, they organized a concert, and planned to hold it in Wallkill. But the town objected, and the location was changed to a farm owned by Max Yasgur in White Lake, a section of Bethel, New York. Somehow, the name "Woodstock" stuck.

The eleventh-hour change of venue made for logistical chaos. Also, while 186,000 advance tickets had been sold, it became clear that many times that number were on their way. One of them was Mr. Burstein.

"I flew to New York and started to hitchhike to Bethel," Mr. Burstein told us. "I finally found an off-duty New York taxi driver who had been hired to deliver ice cream to the festival. But when we got to the New York Thruway, there was a massive traffic jam. The ice cream began to melt. The driver got out and started selling it. When he was finished, he told me he was going back to the city, and said 'you're on your own, kid.'"

A magazine advertisement for the festival

And so, Mr. Burstein began a ten mile walk to Bethel. He wasn't alone. Tens of thousands of other concert-goers abandoned vehicles and made the same trek. Weston's Tom Failla was part of the throng.

"I was a reporter for the Bridgeport Post," said Mr. Failla. "I convinced my editors that Woodstock would be a big story, and they sent me with a photographer. But we got stuck on the thruway and walked the last ten miles."

"I walked and walked," said Mr. Burstein. "You didn't have to wonder where to go. It was obvious. Thousands of people were going the same way. The nice thing was that people talked. You got to know lots of interesting people."

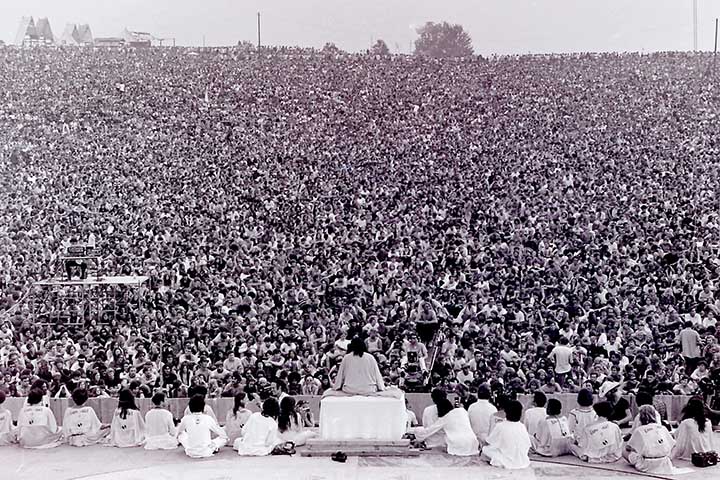

Meanwhile at the festival, organizers surrendered to the inevitable. The fences were taken down, the concert became free. Somewhere around 400,000 attended. Tens of thousands more never got in.

Amenities were scarce. "It was hard to find food and water," said Mr. Failla. "It wasn't like Coachella," said Mr. Burstein, who has attended the desert concert. "You probably couldn't pull off Woodstock today," he said. "Today, you have to provide food, accommodations, security, artisanal sandwiches, and speeches about good causes. You have to have hotels nearby. Woodstock had none of those things."

"But then again, you don't need much to get by for three days when you're fifteen," Mr. Burstein added. "I had a sleeping bag. That's it."

Mr. Failla and his photographer had blue tarps. They slept under them during Woodstock's famous rains. "We camped in an open field," he said. "One morning I woke up, pulled back the tarp, and all I saw above me was cow udders." A herd had wandered into the area, oblivious to the sea of humanity surrounding them.

What the festival did have was fantastic music. Both men remarked on the opening act, Richie Havens, who had moved into first position with a longer set than planned because so many musicians couldn't reach the site. But he began to run out of songs he knew. His remarkable performance of "Freedom," largely a take on the spiritual "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child," was created impromptu. Only some time later, upon seeing the documentary, could he remember how it went.

It began with a swami

Monday's closing performance by Jimi Hendrix – including a searing guitar solo of the Star- Spangled Banner – was equally memorable for both men, who stayed to the end, long after most of the crowd had left. "I can close my eyes and remember it clearly," said Mr. Burstein, "even though I saw it from a distance."

Mr. Failla remembers being stunned by Janis Joplin. Mr. Burstein takes issue with those who believe if you remember the music, you weren't there. "I remember it all," he said. "It was incredible. I was a huge Arlo Guthrie fan. I knew all the words to 'Alice's Restaurant.' Everyone knew the words to Country Joe's 'What are We Fighting For?' Joe Cocker was tremendous. Carlos Santana was amazing. The Who performed 'My Generation' at dawn, and it perfectly expressed the power of my generation."

"There was a great sense of power in a group that size," said Mr. Burstein. "We were united in being against the war, for civil rights, for women's rights, against Nixon, and for a more peaceful world."

And yes, there was a lot of nudity, sex, and drugs. "Much more than they let on in the movie," said Mr. Burstein. "I wasn't part of the drug culture hippie scene," he said. "I didn't want to get involved in all that, and I didn't want to get in trouble. I wanted to hear the music and take in the experience."

It was "amazingly peaceful," said Mr. Failla. "I hung with a lot of interesting people," said Mr. Burstein. "When you walked away for a break, people watched your stuff. It was a very bonding experience."

"At one point," said Mr. Failla, "a National Guard helicopter flew over. A soldier leaned out and gave everyone the peace sign. Incredible."

Mr. Failla managed to find a telephone to call in his bulletins to the Bridgeport Post. "A lot of reporters were there, but we were one of the few newspapers that had continuous updates," he said. "The Associated Press had motorcycle couriers to get out the news, but that was about it."

His wife, Kathy, a journalist, was also at Woodstock, but the two didn't meet there. Ms. Failla served for years as Weston's Town Historian, is active in the Historical Society, and has published photographic books of Weston's history.

After journalism, Tom Failla had a successful career in business, then developed an urge to teach. He is a professor at Norwalk Community College and Pace University.

Mr. Burstein left Woodstock covered in mud and needing to get to New York City. He met two young men, brothers, who offered him a ride to a place he had never heard of: Westport, Connecticut. Mr. Burstein spent the night in their family home. The boys' mother washed his clothes and wanted to hear all about Woodstock. The next morning, she made breakfast, and drove him to Westport's train station. "It couldn't have occurred to me that, a long time later, I would commute from that station into the city frequently."

A longtime Weston resident, Dan Burstein is the author of fourteen books on global economics, technology trends, and pop culture. He was nominated for an Edgar award, and is the founder of Millennium Technology Ventures, a venture capital firm that invests in innovative new technology companies.

We don't know if he ever got around to seeing his sister in Boston.